By Saskia Alais

In November, I was fortunate enough to have been chosen to take part in the Rethinking Migration: from current realities to future challenges training held in the Province of Valencia, Spain. While the focus of the programme leaned towards the research, policies and perceptions of migrants in Southern Europe, the diverse course content allowed me to learn of how migrants fare in countries such as Japan and South Africa. This drove home the fact that the ‘refugee crisis’ isn’t just a European problem, but a global one, that will get worse the longer we continue to ignore it.

By interacting with the other participants on the course who came from a wide range of different backgrounds, such as academics and actors, and who have direct experience of working with migrants, I was able to draw my own conclusions as to how migrants are perceived, what we can do to change the migrant narrative and how best to support newly-arrived migrants. Below you’ll be able to read in more detail my experiences during the 6-day programme that included visiting the Car Mislata refugee centre and the IES Ramon Esteve school in Catadau, that is doing amazing work concerning pupil inclusion.

Social anthropologist, Dr. Karen Hough, delivered the first session of the week by providing an important introduction on how attitudes towards migrants in Southern Europe have changed over time. From there initially being a huge outpouring of humanitarian support in the wake of human disasters such as the 2013 shipwreck near Lampedusa, to EU receiver countries such as Italy and Greece later adopting a more hard-line approach.

A discussion of the Dublin Convention, an EU law that means refugees must claim asylum in the first safe country they arrive in, allowed us to examine how this convention is used by some governments to try and transform the refugee crisis from a European Problem into a Mediterranean Problem. However, little thought is given towards refugees who are sometimes forced to settle in countries where they have little confidence they’ll be able to flourish, thereby making it less likely they’ll be able to flourish.

Thais Maemura and Esther Spaarwater provided important insights into the problems facing migrants in Japan and South Africa, respectively. There is a tendency when talking about migration to think only of Europe, making it easy to jump to the conclusion that migration only happens in that part of the world. Thais and Esther were successful in educating me about an area that I knew very little about.

In South Africa, where half the population lives below the poverty line, migrants from neighbouring countries have found themselves under attacks from locals. In response, the Government launched the National Action Plan to combat Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racial Intolerance in March 2019, in the hopes that this will eliminate these evils from the country within the next 25 years.

Japan used to have a policy called the ‘closed country’ aimed at discouraging migration, until it opened its doors to migrants from countries such as Indonesia in 1975. Despite this, attaining refugee status in Japan is notoriously difficult and many migrants find it hard to integrate in a country that used to pride itself on being culturally and linguistically homogenous.

The issue of migration being politicised is not just restricted to Europe. It happens all across the world, and inevitably when migrants and refugees are portrayed as taking jobs away from the local populace violence and intolerance will always ensue.

Over the course of my stay, I was fortunate to get the opportunity to visit the government run refugee centre Car Mislata in Valencia. Our group was given a tour of the centre by a government official, who helped to dispel some notions most people have of migrants. For example, we were told that 20-30% of migrants in the centre had degrees, up to and including Doctoral level. However, discrimination in employment and housing in addition to other challenges such as learning the language or getting foreign educational certificates officially recognised meant that some migrants were doing jobs they’d never have considered doing in their home countries.

We had a chance to see the type of accommodation provided in the centre, as well as some of the classrooms, dining area and library. While I enjoyed my visit immensely, I couldn’t help but be a bit saddened considering the human cost to so many migrants who survive the journey of making it to Europe but are placed in the situation of having to start all over again. While I admired their resilience I wish that there were more resources in place to ensure every migrant is given the opportunity to fulfil their potential.

Shortly afterwards, our group paid a visit to the Jesuitas to find out some of the work they do with refugees. What I really enjoyed was hearing about the efforts they’re making to bring the locals and refugees together. Everyone is guilty of having their own (maybe not so positive) perceptions of certain groups, and some of their activities include giving everyone in the community the chance to learn about each other.

In the middle of the week social researcher, Dr. Chiara Manzoni, delivered a presentation on the integration of migrants in schools. It’s very easy to lump migrant children together, but one of the key points I took away from this session is that migrant children come from a range of different socio-economic backgrounds and have often been educated to different standards.

Obviously, this places additional pressure on schools on how to ensure migrant children receive an equitable learning experience. Some of the methods used to make migrant children feel more included was the appointment of language ambassadors, dog therapy, one to one tuition, bilingual teaching assistants, breakfast clubs and most importantly chatter groups for parents. Often a child’s parent may be unfamiliar with the school system, so the chatter groups provide a forum for parents to ask questions in a welcoming space and be more informed when it comes to their child deciding which subjects to choose at A Level or even which universities to apply to.

This session was soon followed by a visit to the IES Ramon Esteve school where five students put on a presentation talking us through the work they do to make their learning environment more inclusive. This involves appointing students to sort out any disputes and also fostering values such as respect, toleration and collaboration. Learning points that can definitely be adopted within the UK school system to ensure all groups feel included and valued.

The next day, Dr. Karen Hough, delivered another fantastic session concerning the sociological dimensions of migrants and refugees. I was introduced to concepts such as digital refugees; the ways in which refugees are using technology to find the safest ways to travel to Europe and access specific services. This led on to a discussion of EU funded project MiiCT (ICT Enabled Services for Migrants Project). It’s an app for migrants aimed at improving their access to key public services such as health, education, welfare and employment. The purpose of the app is to give migrants more agency and control over their own lives, particularly when they find themselves in a country that is not that hospitable to migrants.

I was fortunate to have been present when Dr. Willian Bastenberger, provided a fascinating insight into attitudes towards immigration in Spain dating back to the 1950s. We learned that some refugees are more highly regarded than others, the assumption being that they contribute more to the economy. While often the relationship migrants have with locals is asymmetric rather than integrationist, meaning that the two groups never learn from other one another meaning that prejudices become harder to dispel.

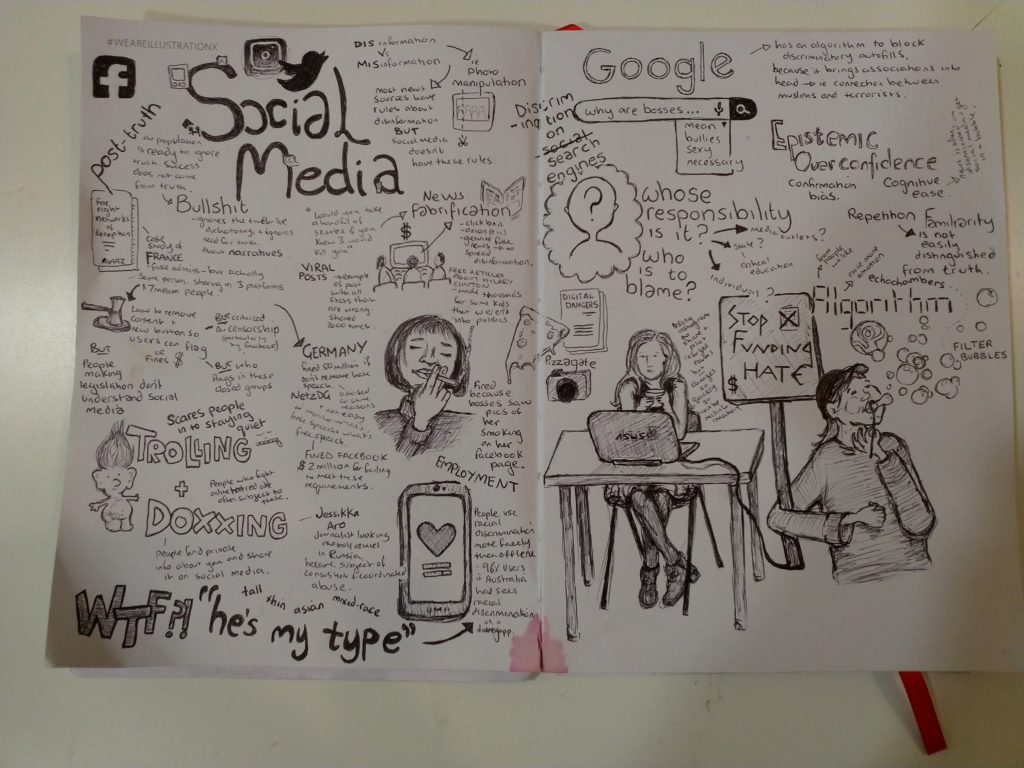

Our next session, focused on Social Media, was delivered by Jessica Sofizade. We learned the difference between misinformation, disinformation and fake news, and how the global presence of social media makes it easier to spread hate and false stereotypes. This has serious implications for how a country responds to migrants, as any politician seen as being too soft on immigration and asylum seekers risks losing their political power given the narrative that surrounds migrants.

From having only a narrow understanding of migration following my completion of the Contemporary Security Issues module at King’s, my knowledge has really grown and I’d encourage members of the King’s Migration Research Group to apply for the next training courses to learn more about what is really a global issue.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions of Kairos Europe, its partners or their employees.

Find Kairos Europe and Rethinking Migration on Facebook

1 Comment